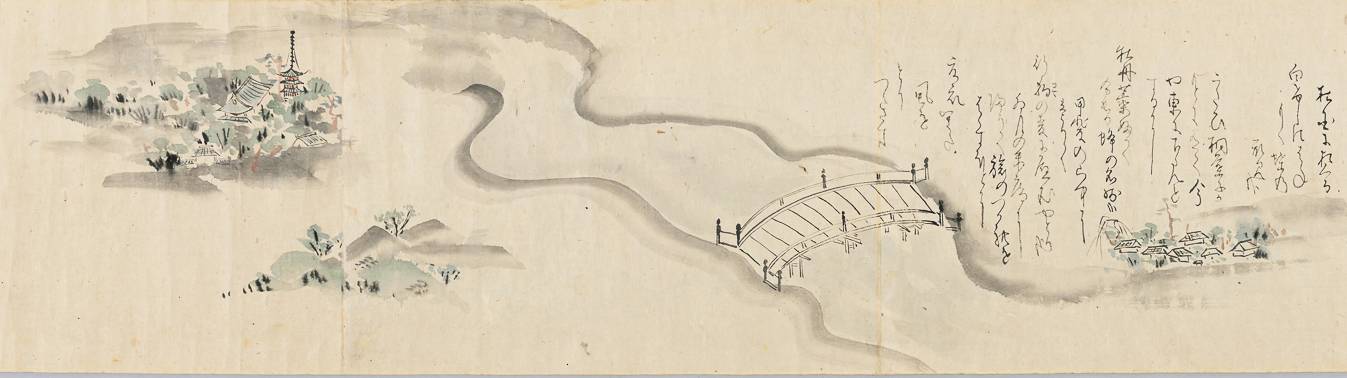

Eternal Travelers

Basho–the famed Japanese haiku master and ‘eternal traveler’ lived in Japan from 1644-1694. His poems are known worldwide thanks to his ability to distill his surroundings and reflections with unforgettable clarity–sometimes humorous, sometimes melancholy. He was a traveler, and what we describe today as a travel writer, documenting his wanderings in diary format or in the form of haibun, a hybrid of brief prose writing punctuated by haiku still employed by writers today, including myself. In the book Narrow Road to the Interior, translated by Sam Hamill, the first of these travelogues begins ,”The sun and the moon are eternal travelers.”

The haibun may be new to readers, but the haiku is a familiar form. I know that I can’t be alone in having compressed to the allowed 5-7-5 syllable lines what was probably the briefest, most lopsided description of nature ever to be printed on construction paper cut into the shape of a leaf. Basho’s haiku haiku are unforgettable–they condense the ordinary world in a string of surprising humor and beauty. What follows is a Basho haiku that is a favorite of mine, the original, and followed by two translations.

|

the original: Kyō nite mo Kyō natsukashi ya hototogisu |

Sam Hamill translation: Even in Kyoto, how I long for old Kyoto when the cuckoo sings. |

Robert Hass translation: Even in Kyoto, hearing the cuckoo cry, I long for Kyoto. |

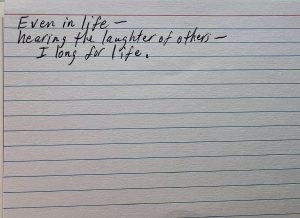

I’m drawn to this poem for so many reasons–I even wrote my own version, which reworks Basho’s poem into a title: “Even in Gretna, Hearing the Cashier Talk, I Long for Gretna.” (You can read at the Academy of American Poets website.) It speaks to nostalgia and that weird sense of loneliness–or sadness?–one might feel when visiting home after a long absence. Present, but absent. Home, but away. The world you thought you knew so well seems different, perhaps–a little rough along the edges, unembellished by whatever fantasies of place that may have taken root in your mind. In one of the prisons I have visited, someone said of this poem: “It’s like being homesick when you’re already home.” Someone else wrote this, which I share with permission:

| Even in life, hearing the laughter of others, I long for life. |

|

Like many things, Basho’s poem takes on a new meaning inside of the world of a prison. Despite the rose bushes and visitor-facing clumps of pansies, stepping into a prison strips colors from the world and makes things seem black and white. The busyness of life outside blurs and loses its sharpness in the mind. Our prisons are banished to the outskirts–on farmlands and former plantations, straddling parish lines, dead-ending on small town roads. They are hard to get to, to get into–by design, of course, but I also have to wonder if prisons are apart in order to keep us from having to see what we have made, from having to witness the embodiment of the lock-them-up-and-throw-away-the-key-mentality. Once inside, once scanned and patted down, once you have signed the book, and slid your ID through a drawer, once you have retied your shoes, once a corrections officer has inspected every sheet of paper, once you squeeze into the limbo between gates, once one gate slams so another can open, you feel heat push you in the face and you follow someone walking faster than you can move through this world of enforced order. This world of where do I look and when do I speak and what do I say. Maybe you are going to the education building, or to the chapel, where they will roll the pulpit aside and set up tables and chairs so that people can write poetry. Time in prison feels different–you have to make it into something.

Because I want to use my time wisely, I always begin a Lifelines Poetry workshop with a plan. That plan is in the form of a two-sided worksheet that has as many poems and prompts as I can fit. I usually include a poem by myself, and if I have been able to bring a teaching poet with me, I’ll include their poem as well. I’ll change up the poems and prompts based on where I am going, just to keep it fresh. The funny thing about this (and all teaching I guess) is that things never go as planned. This unpredictability is what I like best about teaching–I like to be in a situation that requires me to listen, think, reflect, change on a dime, to laugh and to change my mind. Haiku make great ice breakers–I can read the room and drop a haiku that feels perfect in the moment, and suddenly there is a poem to copy into notebooks and tablets, to sink teeth into, to inspire.

~~

In what ways are you an eternal traveler? What topics or memories or places do you circle without ever quite arriving? I keep returning to these places I have visited, circling back. The prison libraries where I was offered carrot cake and Cheetos, the cool room where the men couldn’t stop talking about birds–faded memories of Audubon’s swallow-tail kites, the crows of summer, able to lift off from the prison yard at will. The offered bottles of water, the circles of chairs, the classrooms with padlocked file cabinets, the dimly lit room where an outsized rubber plant of waxy, jungle green seemed to lean in to our conversation, listening.

Wild birds of the mind

soar in the prison chapel’s

dark, forgotten sky.

One thought on “Eternal Travelers”

Great post, Alison. The sense of “eternal travel” outlined here puts me in mind of the flâneur, but there remains that terrible tension between the desire to move through a space and (re)witness and (re)experience a place or thing while prisons confine, resist inquiry and are hidden. Thanks for doing and sharing this work.

Comments are closed.